Idealist philosophers of the nineteenth century shared a certain conception of a person’s good. It can be found in Fichte and Hegel, and then later in Britain in Bradley and Green. In Green, as in these other Idealists, it fits into a philosophical scheme that has far-reaching metaphysical as well as moral dimensions.

Each philosopher presents a distinctive picture: Green’s picture 1s arguably more like Fichte’s than Hegel’s, and is quite different from Bradley’s. None the less, all of them belong to a single album, so to speak, a series of connected efforts to picture how individuals in modern societies can live reconciled or unalienated, and spiritually fulfilling, lives. This series is one of the important products of ethical thought in the nineteenth century; it is a resource that can still greatly benefit present-day ethical and political reflection.

I am not assuming, in saying this, that we can or cannot, should or should not, attempt to renew this vision. It is not obvious that there is a way in which modern individuals can live ‘spiritually fulfilling’ lives, or find the reconciliation with each other that Idealists hoped for, or even that this is something to be aimed for. On the contrary, these issues are pressing and unresolved, perhaps not finally resolvable. When one considers Idealism’s influence in its time, and then its aftermath, it is easy to see it as a vision that failed. It played virtually no role, political or philosophical, in the ‘short’ twentieth century.

Philosophically, it was followed by plenty of twentieth century theorizing about the absurdity and meaninglessness of life; practically, by plenty of evidence of the way life is atomized and commodified in stable modern democracies. One inevitably wonders, in the light of that experience, how to respond to Green’s perfectibilist faith in human potentialities.

All the same, Idealism is attractive. It places self-realization, understood the moral development of the individual, at the center of liberal ethics, by; is sufficiently rooted in an analysis of modernity, and in particular of the Politics of modern societies, not to seem merely anachronistic, or of purely Persona] interest.! It is a social as well as a personal moral philosophy. When contrasted to it, the many contemporary varieties of ‘ethically neutral’ liberalism can easily seem evasive and tinny. They give no account of how people in present-day liberal democracies can and should lead fulfilling lives, or of how a liberal civic framework should provide sustaining conditions for that.

Immediately, of course, one can respond by asking, is that bad? Is it sensible to look for the kind of ethical and civic vision that Idealism tried and mostly (though by no mean wholly) failed to make into a public ideal? Would it have been g good thing if it had succeeded more? Should liberal political practice tie itself to a positive conception of individual good?

Must not hard twentieth-century experience make one a pessimist about people, and a sceptic about how thick or substantial the public ethos of a modern State should be? Liberalism, we may remind ourselves, is first and foremost about resisting tyranny from wherever it comes—the State, an oligarchy, or the people. A robust combination of ethical neutrality, rule of law, and the free market may be the only safe liberal way.

These continuing dilemmas about the ethical basis of liberal politics arouse my own interest in the Idealist conception of a person’s good. Not that Idealism is the only liberal legacy to be explored; the choice is certainly not neutrality or Idealism. The Idealist tradition-cum-critique is important, but other proponents of a comprehensive liberal ethic, and other critics, are as important. I am convinced that a general rethinking of all these late modern ethical ideas is timely, and that such rethinking (which is already going on) can be fruitful for politics in present-day liberal democracies.

In comparison to this rather vast agenda, however, my aim here is very limited. I will re-examine the main themes of Green’s version of the Idealist conception of individual good and ask how well they stand up. My focus will be ethical, not metaphysical or political, and more contemporary than historical. I do want to end by asking what influence on us Green’s conception of a person’s good should have and to indicate a response (though I certainly won’t give a full one). But I shall mainly be concerned to set some of it out as defensibly as possible and then to explain, rather more critically, its structural role in his moral philosophy and its influence on his liberal outlook.? Let’s begin by noting some of its main features.

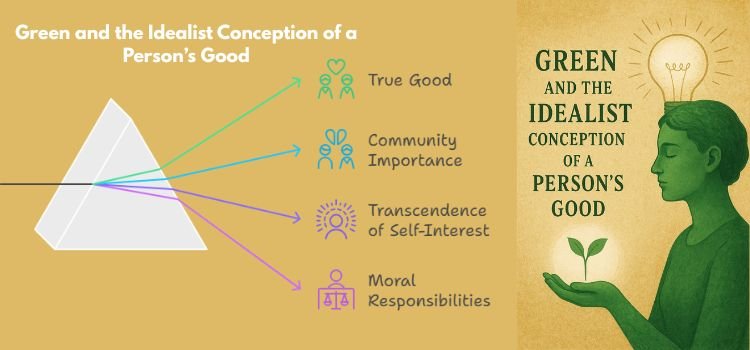

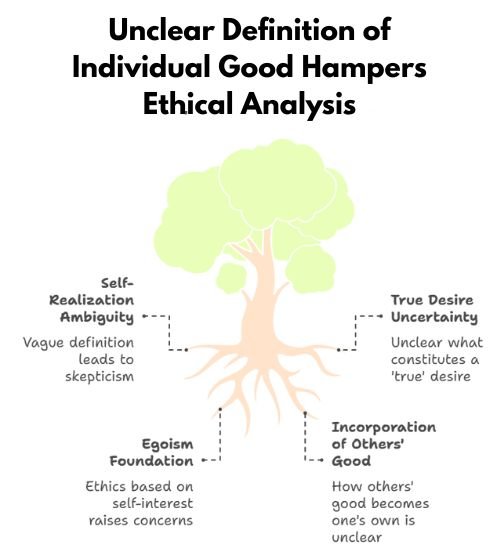

1. The Idealist conception, in Green’s account, as in others, takes it that the good of a person consists in self-realization, and that self realization is freedom. Neither of these claims has an immediately evident meaning. Both give rise to scepticism and suspicion. What is it to realize oneself anyway? And what is so good about it? What if I’m not interested in realizing myself? And why should this rather obscure thing, whatever it is, be called ‘freedom’? Doesn’t it introduce a notion of freedom which is quite unclear in comparison to what we all know and feel personal freedom to be—and one that is all too open to manipulation by well-intentioned interventionists, and convinced political or religious dogmatists?

2. According to Green, one’s true good is the realization of what one ‘truly’ or ‘really’ desires—so self-realization is realization of one’s true desires. Here too suspicion is easily aroused. What is a true desire, and is all and only that which I truly desire a part of my good?

3. There is, in Green’s view as in that of other Idealists, no need to posit, as an underived principle in practical reason, a postulate of impartiality which says that the good of any one individual has no inherently greater reason-giving force than the good of any other—not even in the shape of an ‘impartial point of view’ that is both indispensable for ethics and yet also irreducible to the true interests of an individual moral agent. Green’s ethics rests firmly on a basis of formal egoism. What the self has reason to do, according to the formal egoist, is to pursue its own good. This is the only ultimate practical reason-giving consideration.

4. But then a particularly strong theme in Green is that the good of other persons and things can become a part of one’s own good. One finds this also in Hegel, and indeed in Mill, who was no Idealist. Once again suspicion is aroused. How can another’s good be a part of mine? Isn’t this a metaphor that cries out for explanation?

5. Green thinks that virtue is best for the individual—thus far following the eudaemonist tradition. But he insists, in a way unknown to classical thought, that virtuous action consists in contributing to a good which is common to at individual persons—a good for which there can be no competition.

This mean that the notion that others’ good can become one’s own has a systematic or structural importance for Green which it does not have for Mill. It is an essential part of the reconciliationist project that is central to Green’s moral philosophy.

The truer my understanding of my own self and my own good, Green thinks, the more I understand its identity-in-difference (metaphysically speaking) or differentiated at-one-ness (ethically speaking) with other selves and their good.

My own true good is ‘the common good’, I achieve it by being and doing good—this not because of the rewards offered in an after the, but in virtue of an identity-in-community with others which can be seen to hold through purely metaphysical and ethical reflection.

It is a strange, and characteristically idealist, feature of this vision that in pursuing one’s own realization, one seems eventually to leave one’s own self behind. Self-realization, it turns out, is self-transcendence. No doubt Idealism takes itself to have the means to preserve individuals in their particularity, even as it transcends their distinctness. Identity-in-community is differentiated identity.

None the less, it provides a philosophical vocabulary for an ideal of self-renunciation which is (in one sense of that confusing word, ‘individualism’) anti-individualistic; this is fundamental to its spiritual appeal. Green, like Fichte, belongs to its activist division, as against the contemplative or mystical division to which Bradley belongs. By means of social activism, and personal struggle towards the moral ideal, individuals break the chrysalis of their particularity and fly towards a common home.

This yearning for a common home, for at-one-ness, comes across as strongly in Green as it does in Marx’s occasional rhapsodizing about Communist society—in fact, Green is more single-minded in his conception of it and works it through in his philosophy with more moral fervour.

The yearning for reconciliation is in general one of the most striking (and momentous) leitmotifs of nineteenth-century ethics. Which is not to say that it is coherent. Like many other critics, I don’t think that Green’s conception of the common good ultimately makes sense. However this very important reconciliationist theme will occupy us only tangentially here.

Nor do I think that ethics can be founded on formal egoism; contrary to Green, I think a fundamental—i.e. underived—principle of impartiality is indispensable in our ethical thought. There are reasons for acting that are in no sense whatever grounded in formal egoism. So I don’t want to defend point (3) above, and in fact I will try to indicate how it distorts Green’s ethics. But again, such a very fundamental issue is too big to be treated in its own right here. I am going to restrict myself to providing some defense, though not a full defense, of points (1), (2), and (4). I begin with point (2).