In her book the Sovereignty of the Good Iris Murdoch remarked that moral philosophy often presupposes a philosophy of mind and a metaphysical doctrine. Certainly this is the case with T. H. Green. But in what way do Green’s philosophy of mind and metaphysics enable a deeper grasp of his moral philosophy? They do, I believe, but the question is what kind of conception of moral philosophy do they give rise to? Although my focus is on the writings of T. H. Green, many of the points made in this essay are also of relevance (with some qualifications) to other Idealist thinkers.

Philosophical Ethics and Ethical Practice

The Article initially sketches (very briefly) a distinction between philosophical ethics and ethical practice. It then explores two arguments which appear within Green’s ethical and metaphysical writings: I call these the ‘grey on grey’ and ‘injunctive’ arguments. These terms will be explained more fully in subsequent sections. Basically, the injunctive argument is premissed on the idea that there are clear substantive ethical injunctions present in Green’s moral philosophy.

In this case, the individual moral philosopher has a positive role to play in arguing for certain kinds of moral action over others. Prima facie, the ‘grey on grey’ argument can be interpreted as a metaethical thesis which explains the nature of moral language. However, I contend that the ‘grey on grey’ argument is much more complex than at first appears.

There are a number of different ways to interpret the argument. As indicated, one cruder way is to understand it simply as a metaethical thesis; I argue against this. Another path of argument reads it as containing strong, if indirect, implications for ethical practice. It is this latter body of argument which wall occupy the bulk of this chapter.

Philosophical Contradiction and Green’s Work

It is important to realize immediately that Pam arguing that one can unearth quite legitimate philosophical reasons for both sets of argument in Green’s oeuvre. Although it might look as if am examining an overt philosophical contradiction in Green’s work, I contend that it is more likely to be a problem concerning the fact that Green in dying comparatively young and never being able to complete his work systematically was never able to develop his arguments adequately in this area.

We can then only speculate as to how Green might have resolved this issue. But I still contend that there is a philosophical issue here, in the interpretation of Green’s work, which needs to be explored. Having laid out the above two arguments, the discussion elucidates the crucial metaphysical underpinnings of the ‘grey on grey’ thesis and its relation to Green’s central doctrines of thought and the eternal consciousness. It then turns to the philosophical repercussions of Green’s articulation of the ‘injunctive’ argument.

Metaphysical Anxiety and Final Section

One of the key metaphysical anxieties embedded within the injunctive argument is then illustrated through one of Green’s last writings. The central philosophical problem of the chapter is then briefly restated. The final section sketches an alternative way of articulating Green’s understanding of ethics. This alternative view, in effect, makes another case for the ‘grey on grey’ argument, whilst downplaying the metaphysical role of the eternal consciousness.

This latter section, though, is a purely speculative sketch which minimizes the role of direct moral injunction in Green’s philosophy. This point alone would unsettle many contemporary interpreters of Green. The chapter concludes on a sceptical note with regard to how Green viewed the issues.

The Status of Ethical Concepts

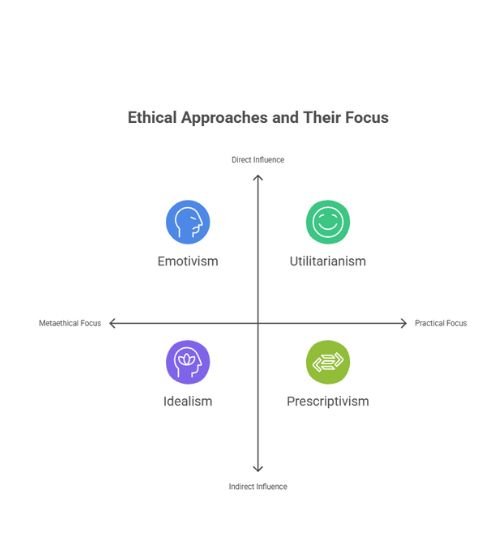

There is an initial distinction to note here between a philosophical ethics implying some form of meta-level analysis concerning the status of moral concepts, which has no necessary bearing on moral practice, and an ethics which is intimately and practically focused on motivating and initiating moral conduct. On the first count, one can conceive of philosophical ethics as simply an explanation of the nature of moral language. In one sense, a great deal of twentieth-century ethical argument has been focused on this.

Doctrines such as naturalism, emotivism, descriptivism, prescriptivism, contractualisim, or rational choice have often had strong metaethical connotations. The other broad dimension of ethical argument is that which is concerned directly with the kind of moral injunctions which ought to govern moral conduct. In other words, the real content of an ethics should be ‘how we ought to live or conduct our lives’.

Modern utilitarianism and much neo-Kantianism have been particularly active in this field—in what I call here the injunctive argument. A philosophical ethics worth its salt should, according to the injunctive argument, provide rigorous justificatory reasons for specific kinds of conduct.

Metaethical Role of Ethics

The metaethical role of ethics is not necessarily totally precluded from the more engaged practical reading. It has been a standard practice in much justificatory ethical argument over the last century to first explain moral language at a metaethical level and then recommend or try to persuade the audience, with good reasons, why one ethical approach is superior to another for governing or guiding moral conduct. Admittedly, some arguments would not be terribly helpful on this point. For example, if, having convinced one’s audience that ethical propositions are just emotional effusions, it is difficult to see how one could offer any clear concrete reasons as to why one might morally effuse one way or another.

Idealism’s Unique Reading

However, it is important to lay stress on the point that there are different philosophical accounts of the relationship between philosophical ethics and ethical practice. Idealism has its own unique reading of this relationship. Further, not all such Idealist arguments should necessarily be characterized as metaethical. This point is crucial to the argument of this chapter. In the case of emotivism, the point is that meaningful propositions can really only be found in the spheres of logic, science, or mathematics. Ethical propositions, in practice, being emotive, are seen as unenlightening (except in so far as they tell us about the psychological state of the utterer). In the case of prescriptivism, there are reasons as to why we act morally, but these are not empirical reasons.

Idealism, as indicated, has its own reading of the relationship between philosophical ethics and ethical practice—which I link in this chapter with the ‘grey on grey’ argument. This latter argument forms part of the core conundrum of this essay. I would not associate this argument with metaethics, the fundamental reason being that one important interpretation of the ‘grey on grey’ argument still embodies a practical articulation of ethics.

However, it is not the expected understanding of the terminology that one encounters in, for example, the more common direct injunctive form of moral argument. It is a more indirect understanding. This point contains the core problem of Green’s ethics. Put very crudely, the ‘grey on grey’ argument gives a substantive, if indirect, philosophical priority to ethical practice (over and against direct injunctive ethical argument).

Grey on Grey as Embedded Ethics

The ‘grey on grey’ thesis thus articulates an ethics which is embedded in ordinary established moral practices. It is an ethics which is understood only indirectly, usually ex post facto, by the individual moral agent. But it is still fully active in the world.

One important rendition of this ‘grey on grey’ argument which forms a central theme in this chapter—is also closely linked to the metaphysical arguments about the eternal consciousness and the epistemological doctrine of thought. I call this the stronger rendition of the ‘grey on grey’ argument. The softer rendition (which is linked to a social practice argument) is something I pursue mainly in the more speculative final section of the chapter.

Idealism’s Moral Reputation

Despite the above ‘grey on grey’ perspective (and its strong philosophical underpinning in Green’s metaphysics), Idealism has an overt reputation—particularly in a writer such as T. H. Green—for being overly forthright about what we ‘ought to do’, and seeing a very positive injunctive role for moral philosophy. British Idealists particularly have often been seen by posterity as almost overly moralistic in this injunctive sense. Thus, my interpretation of the ‘grey on grey’ argument might appear oddly out of kilter with one more popular image of Idealist ethics: namely, as embodying necessarily a robust injunctive moral philosophy.