Green claims that the responsible agent acts not simply on appetites or passions but as the result of ought judgements or in Hight of a conception of goods. But he also says that the deliberating agent takes the object of reflectively endorsed desire as his own good indeed, his own greatest good and that he aims at ‘self-satisfaction’.

We may wonder why pursuit of goods or the good has to be understood as pursuit of the agent’s own good. My responsible actions may express my choices, commitments, and conception of the good. But why should I think that pursuing or achieving my conception of the good promotes my own interests? Isn’t this a confusion of the ownership and the content of my aims? Green thinks of pre-deliberative desires as ‘alien’ or ‘other’, and he regards deliberative endorsement as a process of ‘identification’. The objects of deliberative endorsement reflect my sometimes deeply held convictions about what is worthwhile, which will reflect how I think of myself and how I value myself. He seems to believe that I cannot separate thinking that a course of action is worthwhile for me to do and thinking that it is better for me to act that way. There is some force to this line of reasoning, but we may wonder if it doesn’t make the pursuit of a good or the good prior in explanation to pursuit of a personal good.

Book II offers us an account of responsibility—-common to both a good will and a bad will—in terms of the deliberative capacities of a self-conscious mind. But, as Green recognizes, this does not provide an account of the good will or of what distinguishes the good and bad wills . The quality of a person’s will depends upon the content of her will, the objects in which she seeks self-satisfaction .

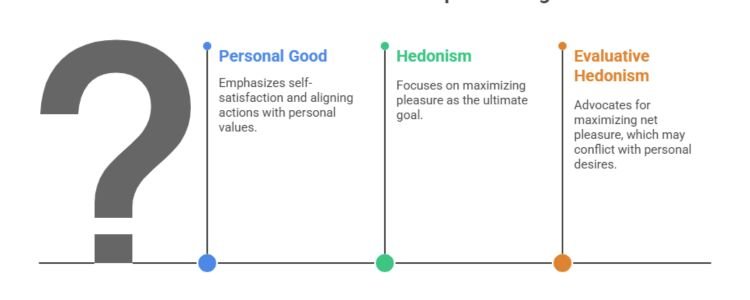

Green spends considerable time explaining what the good is sot. In particular, he is very concerned to reject the hedonism that he finds in the utilitarian tradition and that he associates with a naturalistic approach to ethics. Green interprets Mill as a hedonist, and focuses his criticism of hedonism on Mill’s claims in Utilitarianism. Green’s criticisms of Mill are quite interesting, and often quite subtle and probative, defying easy summary.

One of Green’s main complaints is that the plausibility of evaluative hedonism rests on a commitment (perhaps implicit) to psychological hedonism, which rests on the fallacy, which Butler exposed, of inferring that pleasure is the object of desire from the fact that it is expected that pleasure will attend the satisfaction of desire.

Green thinks that psychological hedonism is prima facie implausible; it seems that we pursue many things other than our own pleasure, and often at the expense of our own pleasure . But, on reflection, this apparent evidence against psychological hedonism may not seem compelling. After all, it seems that we always expect pleasure from the satisfaction of our desires, and that the anticipation of this pleasure can make us desire it . Butler thought that this defense of psychological hedonism was fallacious.

That all particular appetites and passions are toward external things themselves, distinct from the pleasure arising from them, is manifested from hence—that there could not be this pleasure were it not for that prior suitableness between the object and the passion; there could be no enjoyment or delight from one thing more than another, from eating food more than swallowing a stone, if there were not an affection or appetite to one thing more than another.

Butler’s point is that it is a fallacy to suppose that we aim at the pleasure that we expect to accompany the satisfaction of our desires . The pleasure in getting is predicated on the prior desire for ; the desire is not predicated on that pleasure. And even if the anticipation of produces a new desire for , that gives no reason to think that the original desire for is predicated on the expectation of pleasure.

As i think Butler recognizes, and as Green clearly does, exposure of this fallacy does not imply that psychological hedonism is false; rather, it undermines one common source of support for that doctrine. Butler’s point is that pleasure depends upon the satisfaction of desires for various things. But this point does not show that we do not desire these things on account of their (expected) pleasurableness. If we distinguish between ultimate and proximate objects of desire, we can admit Butler’s point and still claim that pleasure is the only ultimate object of desire or, in Green’s terms, the only thing desired intrinsically or for its own sake. However, Green thinks that when this claim is clearly identified and stripped of fallacious defenses, it will seem implausible. Life is replete with examples of people choosing worthy courses despite the expectation of securing the lesser pleasure.

So Green thinks that Mill’s evaluative hedonism rests on a fallacious defense of psychological hedonism . But he also wants to reject evaluative hedonism outright. One argument he makes is that evaluative hedonism is actually inconsistent with psychological hedonism. Evaluative hedonism says that our ultimate aim ought to be to maximize net pleasure or to seek the largest sum of pleasures, whereas psychological hedonism claims that pleasurable experience is the ultimate object of desire. But a sum of pleasures is not itself a pleasure, and so, according to psychological hedonism, we could not act on the requirements of evaluative hedonism. This is a problem for someone who combines both evaluative and psychological hedonisms.