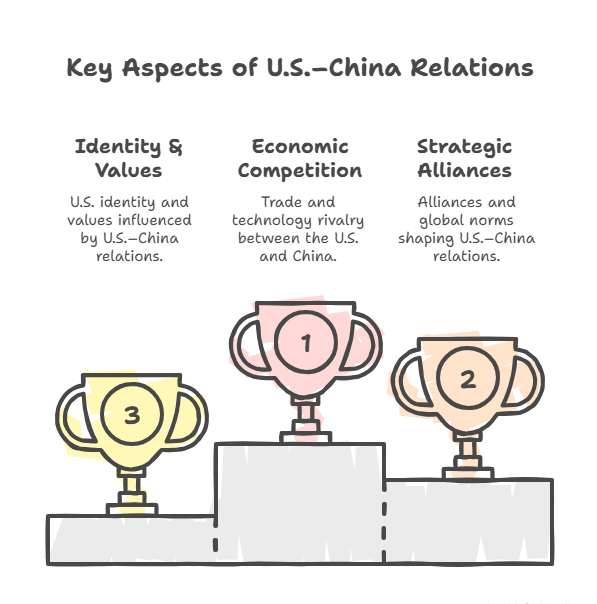

The U.S.–China relationship is arguably the most consequential bilateral relationship in the 21st century. As China’s economic and technological power grow, the debates in Washington, among U.S. voters, and across international institutions are intensifying. Strategic competition in trade, technology, alliances, and global norms is shaping not just policy but identity, values, and the expectations Americans have for their country’s role in the world.

This article dives into how trade and tech tensions are playing out, how the U.S. is navigating global institutions and foreign aid amid these shifts, and how voter opinions—across partisan lines and demographic groups—are being shaped. The goal: to help readers understand not just what is happening, but why it matters, and what may come next.

1. Strategic Competition with China: Trade, Technology, Alliances

Trade & Supply Chains

Trade is the backbone of U.S.–China relations, but in recent years it has become a source of contention. America has increasingly focused on reducing dependency on Chinese supply chains in sensitive industries, especially semiconductors, AI-relevant chips, and other advanced technologies. The goal is to protect national security and reduce vulnerabilities.

A study of global supply chain trends covering 2016–2023, for example, shows that while China remains deeply embedded in upstream segments of many global value chains, the U.S. and its allies are pursuing a “China+1” strategy. That means diversifying sourcing to other countries in Asia, Latin America, or elsewhere to reduce risk.

Tariffs, export controls, and trade restrictions have become tools of foreign policy. For example, the U.S. has imposed export restrictions on advanced computing and semiconductor manufacturing to restrict China’s access to critical technology.

Technology & Innovation Competition

Technology is now central to the U.S.–China rivalry: AI, quantum computing, biotech, and data governance are all strategic arenas. Both countries see leadership in these fields as crucial for economic growth, military advantage, and global influence.

-

Export controls: The U.S. has increasingly restricted exports of high-end semiconductors, certain AI-relevant components, and dual-use technologies. These measures aim to prevent China from leveraging U.S. technology for military or strategic uses.

-

Science & tech cooperation vs divergence: There are still formal agreements and channels for cooperation—basic research, some science cooperation—but tighter controls and selective cooperation now dominate. For instance, the U.S.-China science & technology agreement (originally signed in 1979) has been renewed and amended, but recent updates reflect stronger safeguarding and limits in sensitive areas. Ref_Wikipedia

-

China’s push for tech self-reliance: Initiatives like “Made in China 2025” have pushed Beijing toward becoming not just a manufacturer, but a leader in emerging tech sectors—solar panels, high-speed rail, UAVs, batteries, etc. These efforts both worry U.S. officials and force strategic response. (Ref_Wikipedia)

Alliances, Global Order & International Institutions

Foreign policy isn’t just bilateral: it involves multilateral systems, norms, rules, and how countries align themselves. The U.S. is seeking to maintain its influence in global institutions while China is expanding its own role and advocating for alternate norms.

-

Global norms and “rules-based order”: The U.S. has long defended international institutions (UN, WTO, World Bank, etc.), human rights, democratic norms, and relatively free trade. China challenges some of these norms, or seeks to modify them (for example, emphasizing development without political preconditions). These tensions are playing out in diplomatic arenas.

-

China in multilateral institutions: China is increasing its influence via funding, staffing, and engaging in leadership of some multilateral bodies. Meanwhile, U.S. influence is seen by some analysts as eroding, especially when budget constraints, domestic politics, or strategic missteps weaken America’s ability to lead.

-

Alliances in Asia and beyond: The U.S. is reinforcing alliances in Asia (e.g., with Japan, South Korea, Australia), and working through frameworks like the Quad (U.S., Japan, India, Australia) to respond to China’s rise. At the same time, China is pushing its own regional influence, infrastructure investments (e.g., Belt and Road), and security partnerships (Global Security Initiative, etc.).

2. U.S. Participation in Global Institutions, Foreign Aid, & International Norms in Times of Conflict

Foreign Aid: Amounts, Priorities, Perceptions

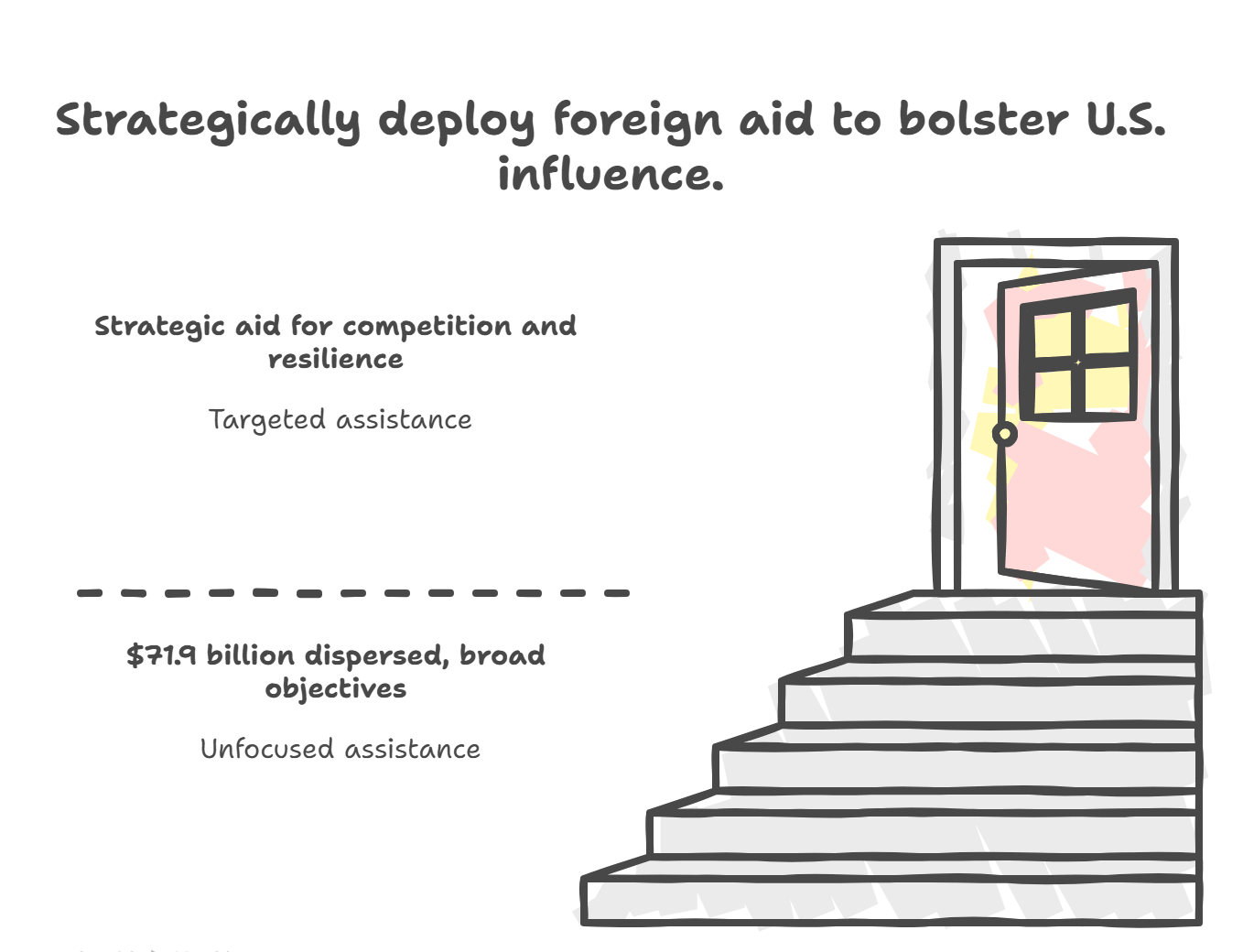

Foreign aid remains a tool of U.S. power and influence—and a contested one domestically.

-

In fiscal 2023, the U.S. disbursed about $71.9 billion in foreign aid.

-

Aid includes humanitarian assistance, economic development, public health programs, and democracy & good governance pr

-

ograms. It also shifts in response to crises—wars, natural disasters, pandemics.

-

One strategic view is that foreign aid should be used more explicitly as part of competition: supporting allies, building resilience, counteracting Chinese infrastructure or investment influence in the Global South, etc. Analysts suggest reforms to how aid is allocated, managed, and delivered to improve effectiveness in strategic competition.

Global Institutions & U.S. Role

-

Rules and institutions under pressure: The post-WWII order, based heavily on U.S. leadership and norms like human rights, free tra

-

de, open sea routes, etc., is strained. China (and other rising powers) challenge elements of it—arguing for development without strictly adopting political values, emphasizing sovereignty etc.

-

China’s alternative initiatives: Programs like China’s Global Development Initiative, Global Security Initiative, and others represent efforts to offer alternate frameworks. These sometimes downplay political conditionality.

-

U.S. internal constraints: Budget woes, disagreements in Congress, political polarization, and public opinion can limit the U.S. ability to lead globally in institutions or to commit large, sustained foreign aid or policy initiatives.

Norms & Conflict

Times of conflict (e.g., wars, disputes over trade,

tech espionage, territorial conflict in Asia) test norms and global institutions. How the U.S. responds in these moments matters for its reputation and ability to shape the international order.

-

Norms around human rights, free expression, rule-of-law are under pressure. U.S. ability to speak credibly on these issues is often challenged when critics point to domestic issues.

-

Issues like AI governance, cyber threats, climate change, global health pandemics require cooperation—but political tensions (both internal and bilateral) make cooperation difficult. Still, there are areas of overlap: both U.S. and China see risks in certain AI misuse, or threats from climate disasters, which can push cooperation even amid rivalry.

3. How Foreign Policy Positions Are Shaping Voter Views

Public opinion plays a big role—not just in framing what is possible, but what leaders are willing to do. How voters see the U.S.’s role with China, what trade and tech policies they support, and how global norms are valued is changing—and these shifts can have electoral implications.

Perceptions of Foreign Aid & Chinese vs U.S. Aid

-

According to Pew Research, Americans tend to view U.S. foreign aid more favorably than aid from China. For many, U.S. aid is seen as more beneficial to developing countries.

-

There is partisanship in these views: Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents are more likely to see aid (both U.S. and China) as beneficial than Republicans. Conversely, Republicans are more likely to view Chinese aid as harmful.

Trade, Technology & National Security Views

Voters across the spectrum are increasingly aware of trade and technology issues not just as economic questions, but as questions of security, values, and national interest.

-

Issues like supply chain vulnerabilities, reliance on foreign tech, export controls, and intellectual property theft resonate with voters who worry about jobs, economic competitiveness, and national security.

-

Many Americans support restrictions on tech transfers when those are perceived to pose security risks—e.g., dual-use technology, AI, quantum computing.

Partisan & Generational Differences

-

Democrats and Republicans differ on how much emphasis to put on human rights, democratic norms, environmental concerns vs pure economic or strategic effectiveness. For instance, some voters want foreign policy that reflects U.S. values as much as it protects U.S. interests. Others are more pragmatic or realpolitik in preference.

-

Younger voters (Millennials, Gen Z) tend to be more supportive of multilateralism, more skeptical of purely transactional foreign policies, more concerned with climate and human rights, more willing to see compromises if they align with global norms.

What Voters Are Asking About

In recent elections and poll cycles, voters are increasingly asking:

-

What is U.S. policy toward China on AI, semiconductors, data privacy, and how transparent / ethical is it?

-

How will the U.S. maintain alliances, especially in Asia, and what are U.S.’s commitments there?

-

How is the U.S. balancing strategic competition with cooperation (global health, climate)?

-

How much is foreign aid serving U.S. strategic interests vs. purely altruistic goals? Is the U.S. still capable of projecting values globally or is domestic politics eroding that?

4. Stakes, Challenges, and What Might Come Next

What’s at Stake

-

Global stability and order: If the U.S. and China drift into constant competition without trust or cooperation, global norms—on trade, human rights, climate action—could fragment.

-

Economic competitiveness: Jobs, innovation, future leadership in AI, biotech, etc. depend on how well the U.S. adapts policies, protects innovation, and manages trade relationships.

-

National security: Technology transfer, espionage risks, cyber threats remain serious. How the U.S. handles these will affect military readiness and strategic deterrence.

-

Soft power and moral authority: The U.S. has long relied on being perceived as a country committed to values—not just interests. If that perception fades, influence in the Global South, in alliances, and in global institutions could wane.

Key Challenges

-

Domestic polarization: With foreign policy increasingly politicized, bipartisan consensus is harder. Policy volatility can undermine credibility.

-

Balancing cooperation with competition: Some issues require cooperation (climate change, pandemics, maybe AI norms), even while rivalry persists. Finding frameworks that allow both will be hard.

-

Resource constraints: Budget limits, public fatigue with foreign engagements, and demands for domestic spending can reduce what’s possible abroad.

-

China’s own strategies: China also pursues its priorities aggressively. Its infrastructure investments, its influence in developing nations, its diplomacy – sometimes offered without strict political conditions – are attractive to some countries.

Possible Future Scenarios

-

Modus Vivendi with Managed Competition: The U.S. and China settle into a relationship which is competitive in many fields (tech, trade, security), but with built-in channels for cooperation, risk control, and crisis management. Some tech decoupling remains, but not radical; alliances strengthen; global norms adapt. (This is one scenario discussed by Carnegie and others.

-

Escalated Rivalry: More sanctions, sharp export controls, competition for influence in the Global South, potential flashpoints (Taiwan, South China Sea) become bigger risks.

-

Selective Cooperation: U.S. focuses on specific domains where values align (climate, health, AI safety), while competition remains fierce elsewhere.

-

Shifting Global Order: If enough countries ally with China’s model (e.g. less political conditionality, more state-led development), the rules-based international order as once conceived may undergo significant revision or fragmentation.

5. What Americans Should Watch for & Why It Matters Personally

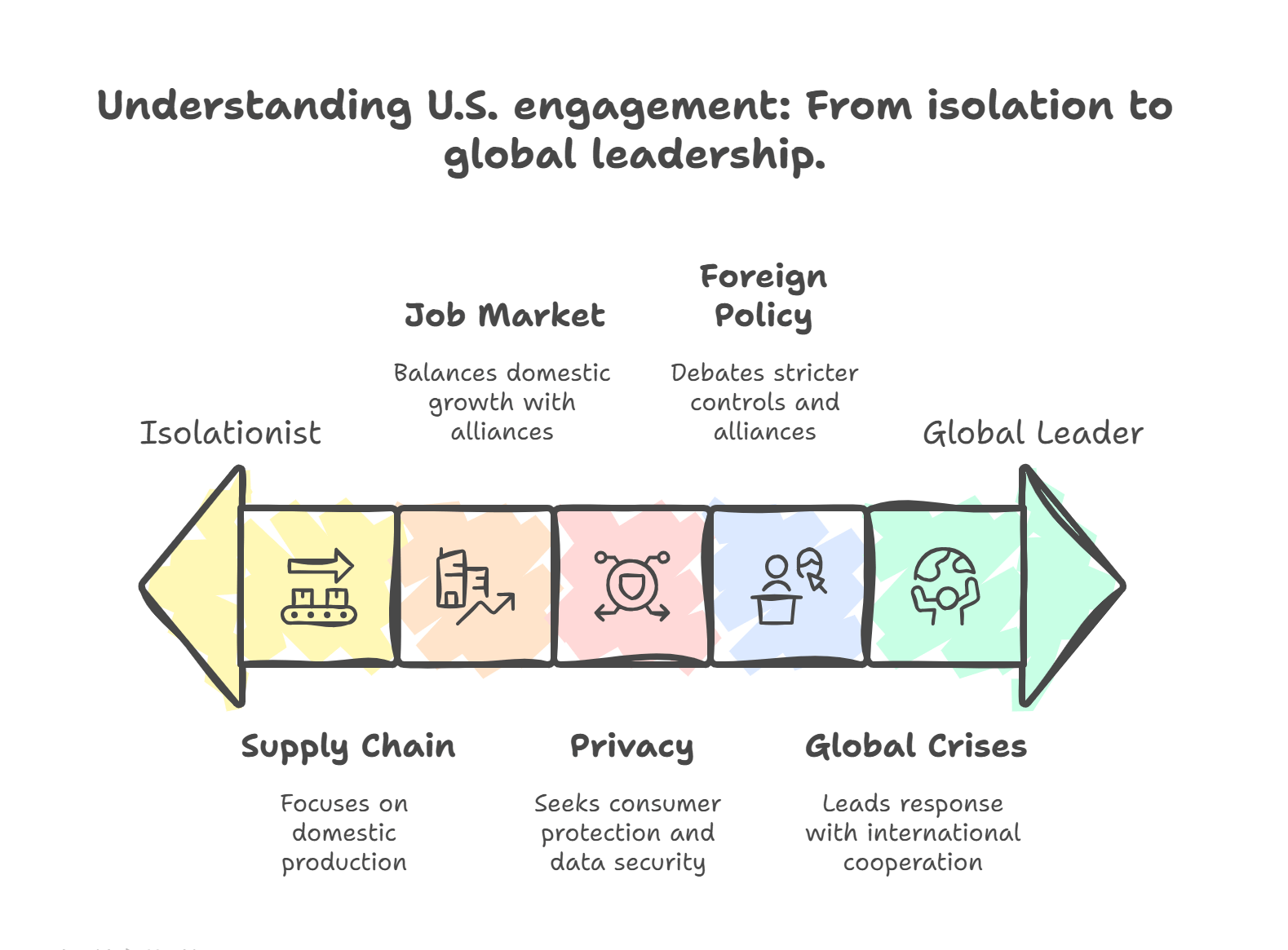

To bring this closer to home, here are practical things readers can look out for and reflect on, and why this matters in daily life.

-

Supply chain disruptions / consumer prices: Tariffs, export bans, shortages of parts (chips, electronics) can affect what goods cost and availability.

-

Job market & innovation opportunities: Where tech research, semiconductor plants, AI labs are located—if investment shifts away from the U.S. toward allied countries—or if the U.S. aggressively builds domestic capacity, that can drive jobs.

-

Privacy, data security: As the U.S. shapes rules around AI, data flows, and technology transfer, what protections do consumers have? What risks are there for surveillance or misuse?

-

Foreign policy debates during elections: Candidates’ positions on China are becoming a litmus test. Voters will want clarity: who wants stricter export controls, who supports broad alliances, who emphasizes values vs. security vs. economic returns.

-

Global crises & U.S response: When climate disasters, pandemics, or humanitarian crises occur, does the U.S. respond as leader or pull back? How much cooperation with China is part of the solution (e.g. climate negotiations)?

U.S.–China relations are no longer a distant strategic issue—they’re deeply woven into economics, national security, technology, and the values we hold as a society. The competition is real, but it’s not zero-sum in every domain. How the U.S. defines its priorities—trade vs tech restrictions, cooperation vs rivalry, values vs interests—will matter enormously in the decades ahead.

For Americans, this isn’t abstract geopolitics. It affects jobs, trade goods in your home, your ability to use technology safely, what values America projects to the world, and how the world views America in return. As you follow news about export bans, debates over foreign aid, Congress discussions on alliances, or upcoming elections, think about what kind of U.S. foreign policy you believe in: more cautious and protective, or more open, values-based, engaged globally?

One thing seems certain: U.S. foreign policy priorities toward China will remain a defining issue for many years. Understanding the strategic tradeoffs, domestic pressures, and global stakes will help you be a more informed citizen, and help ensure that whoever leads reflects not just fear, but vision.