T. H. Green’s Prolegomena to Ethics develops a perfectionist ethical theory that aims to bring together the best elements in the ancient and modern traditions.! Green was heavily influenced by the Greek eudaimonist tradition in ethics, especially by the views of Plato and Aristotle.

He thought the Greeks were right to ground an agent’s duties in a conception of his own good whose principal ingredient is the exercise of his rational or deliberative capacities. Green interprets this aspect of eudaimonism in terms of self-realization. Like Aristotle, he thinks that the proper conception of the agent’s own good requires a concern with the good of others, especially the common good.

However, Green thought that the Greeks had too narrow a conception of the common good. It is only with Christianity and Enlightenment philosophical views, especially Kantian and utilitarian traditions in ethics, Green thinks, that we have recognition of the universal scope of the common good.

This leads Green to claim that full self-realization can take place only when each rational agent regards all other rational agents as ends in themselves on whom his own happiness depends; in such a state, there can be no conflict or competition among the interests of different rational agents.

However inspiring, these claims about self-realization and the common good are rather extraordinary. To assess them, we must understand Green’s perfectionism, the role of the common good in self-realization, and the way in which Green’s idealism supports his reconciliation of the agent’s own good and the good of others.

My reconstruction of these issues will appeal in part to Aristotle’s claims about eudaimonia, friendship, and the common good, on which Green’s own views about self-realization and the common good draw.

Self-Consciousness and Responsibility

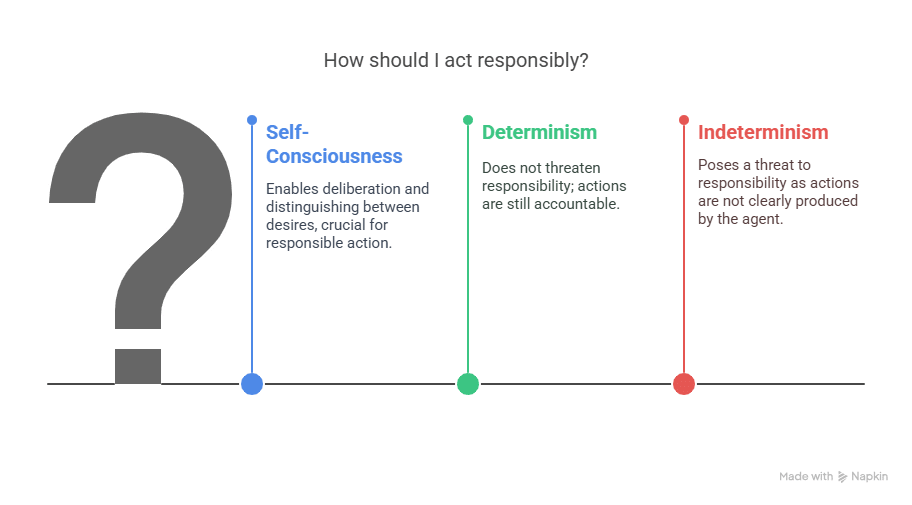

Green’s ethics of self-realization depends on his understanding of the role of self-consciousness in responsible action. Though it is common to think that moral responsibility is threatened by determinism and requires indeterminism, Green denies this. Indeed, he thinks that indeterminism is a greater threat to responsibility, inasmuch as it is unclear why we should hold a person accountable for actions that are not produced by his article.

Responsibility neither is threatened by determinism nor requires indeterminism; it requires self-consciousness. Moral responsibility requires capacities for practical deliberation, and practical deliberation requires self-consciousness.

Non-responsible agents, such as brutes and small children, appear to act on their strongest desires, or, if they deliberate, to deliberate only about the instrumental means to the satisfaction of their desires. By contrast, responsible agents must be able to distinguish between the intensity and the authority of their desires, to deliberate about the appropriateness of their desires and aims, and to regulate their actions in accord with these deliberations.

Here, as elsewhere, Green shows the influence of a long tradition of thinking about agency that extends back to the Greeks and is given forceful articulation by moderns, such as Butler, Reid, and Kant.? This requires that one be able to distinguish oneself from particular desires and impulses—to distance oneself from them—and to be able to frame the question about what it would be best for one on the whole to do.

Green thinks that the process of forming and acting on a conception of what it is best for me on the whole to do is for me to form and act from a conception of my own overall good.

The Role of Deliberation in Moral Action

A man, we will suppose, is acted on at once by an impulse to revenge an affront, by a bodily want, by a call of duty, and by fear of certain results incidental to his avenging the affront or obeying the call of duty. We will suppose further that each passion suggests a different line of action.

So long as he is undecided how to act, all are, in a way, external to him. He presents them to himself as influences by which he is consciously affected but which are not he, and with none of which he yet identifies himself. So long as this state of things continues, no moral effect ensues. It ensues when the man’s relation to these influences is altered by his identifying himself with one of them, by his taking the object of one of them as for the time his good. This is to will, and is in itself moral action.

In claiming that a moral effect ensues just in case the agent reflectively endorses his appetites, Green is not saying that reflective endorsement is sufficient for morally good action; rather, that it is sufficient for morally assessable or responsible action. In fact, it is not clear that he means to say that action is responsible only when it is the product of reflective endorsement. Presumably, we want to hold people responsible for those actions for which they had the capacity for reflective endorsement.

Deliberative Self-Government and Non-Naturalism

So responsibility or moral agency requires deliberative self-government, and this requires self-consciousness, where self-consciousness involves the ability to represent these different impulses as parts of a single psychological system and recognition of the self as extended in time and endowed with deliberative capacities. And because Green believes that what is not itself an element of consciousness is non-natural, he appears to agree with Kant that responsibility presupposes non-naturalism, even if his reasons for accepting non-naturalism are somewhat different. It is in this way that responsibility presupposes deliberative self-government, self-consciousness, and non-naturalism, rather than indeterminism.

Green considers the apparent threat to responsibility resulting from the claim that agents necessarily act on their strongest desires.

He thinks that the threat is specious, because it rests on an ambiguity. The intensity of some desires is stronger than that of others; their force is stronger, The action of non-responsible animals is just the vector sum of these forces; they do act on their strongest desires, in this sense. But responsible agents, who can distinguish between the strength or intensity of a desire and its authority and act on these judgements, need not act on their strongest desire. Green associates regulation of one’s actions by such deliberations with strength of character, and claims that strength of character can overcome strength of desire. But strength of character, Green thinks, is no threat to responsibility; rather, it is a pre-condition of it. It is only by failing to distinguish between these two different kinds of strength, Green thinks, that one could see a threat to responsibility here. Another way to put Green’s point is this.

The claim that one must act according to one’s strongest desire either

- (a) associates strength of desire with its felt intensity or

- (b) associates it with whatever desires move one to act after due deliberation.

On the

- (a) reading, the alleged necessity of acting on one’s strongest desires would threaten responsibility, but is false; whereas on the

- (b) reading, the alleged necessity is trivially true, but no threat to responsibility.